Heart of Darkness, the haunting novel by Joseph Conrad, gives readers a glimpse of Africa at the turn of the 20th Century Africa—its mist shrouded waters, impenetrable forests, exotic wildlife, and rapacious colonial rulers. It shows us little of Africans, however. Europeans are the central characters; Africans are nameless. Most are part of the faceless mob—simple minded, devoid of culture, inscrutable, objects of pity. We see Africa but not Africans.

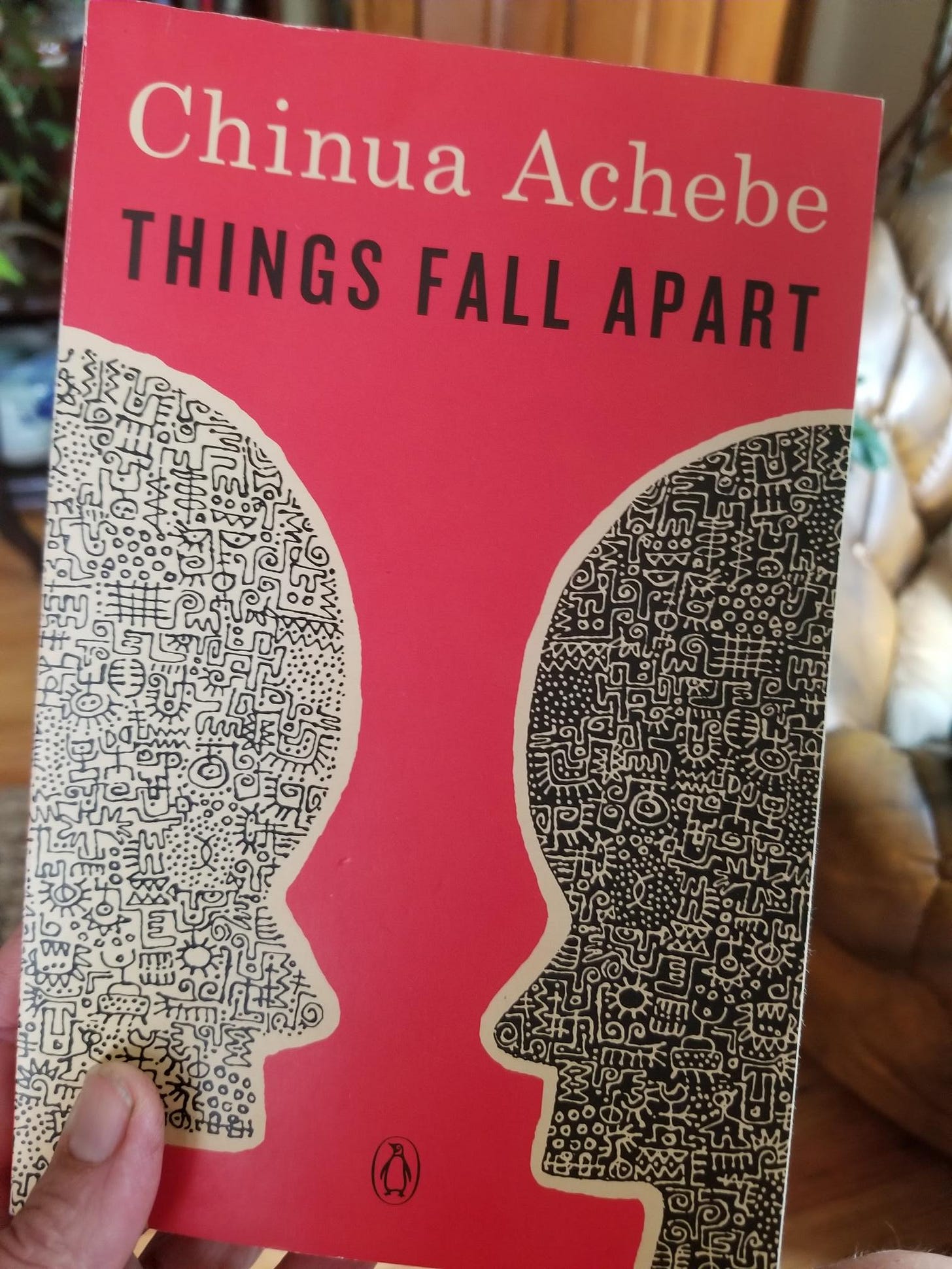

Conrad was not alone in this omission. Other 20th Century European authors did likewise. Their critiques of the abuses of colonialism, however laudable, tended to underscore the impression of Africa as a dark continent in need of light. Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe could not help but notice. His rejoinder came in the form of a novel, Things Fall Apart, published in 1958.

Achebe portrayed the precolonial Igbo culture of lower Nigeria as anything but savage. Rather, the nine fictional Igbo villages have institutions for resolving conflict, marks of status, religious obligations, gender division of labor, community celebrations, marriage and funeral rites, sporting events, artistic expression, proverbs, and traditions. He also imbued his characters with depth and force of will. They experience close friendships, worry about the next generation, feel anxiety over status, and experience grief, pride, despair, and happiness.

Achebe does not idealize Igbo culture which elevated manly strength over other virtues, tolerated spousal abuse, and mandated infanticide and human sacrifice under certain conditions. When Western missionaries and later colonial authorities moved to the area, these practices were challenged and ultimately discarded. Western norms are not idealized either. Colonial rule brings injustice, corruption and disproportionate retribution. Moreover, westerners do not seek to understand that which they seek to replace and their arrogance is a destructive force.

Things Fall Apart is not merely a portrait of Nigeria at the dawn of the Colonial Era from an African perspective. It is a story with universal appeal, a Shakespearian tragedy about a great man with a fatal flaw undone by adverse circumstances. It is about pride and loss in a time of change. It is about being a casualty of social upheaval.

The book’s main character is Okonkwo of the Umuofia clan, a self-made man of wealth and status. Despite his success, Achebe writes, Okonkwo’s “whole life was dominated by fear, the fear of failure and of weakness…the fear of himself, lest be should be found to resemble his father.” His father, Unoka, died penniless and in debt and Okonkwo was ashamed of him.

Okonkwo vowed he would never be like Unoka. Where Unoka was weak, Okonkwo would be strong. In his youth he was renowned for his wrestling ability. Where Unoka was a coward, Okonkwo would be a warrior. He took the most heads in battle. Where Unoka was gentle, Okonkwo would show no affection even for those he loved. Where Unoka was lazy, Okonkwo would be tireless. From nothing he worked to become one of the wealthiest in his clan. His barns were full of yams, his three wives had many children, and he was respected by all. He had earned three of the four titles a man could earn. Only one or two men in a generation earned all four; they were considered lords of the clan. Okonkwo believed he would one day achieve this. He would not, however. His fear would undo him.

The story begins when a 15 year old boy comes to live with Okonkwo and his family. To repay the community for the murder of one of its women and thus avoid war, a neighboring tribe offered a virgin girl to the widowed husband and a boy as a sacrifice. The boy, Ikemefuna, was allowed to live until the oracle determined the moment for justice had come.

During the three years he lived in the village, Ikemefuna became a valued member of Okonkwo’s household and a close friend to his son Nwoye. Ikemefuna called Okonkwo father. Although Okonkwo felt affection for the boy, he dared not show it for he considered affection for anyone a sign of weakness.

When the village oracle determined that the time had come for Ikemefuna to be killed, an elder Ogbuefi Ezeudu forewarned Okonkwo and advised him to take no part in it. Okonkwo told the boy he was returning home. Rejecting Ezeudu’s advice, Okonkwo went with the men of the village and Ikemefuna on a walk. After walking for miles, the men attacked the boy with machetes. When Ikemefuna ran to Okonkwo for protection, Okonkwo, fearing that the group would think him weak, killed the boy. When he returned home alone, Nwoyo discerned that Ikemefuna was dead and it embittered him.

Okonkwo was often harsh with his wives and children. “No matter how prosperous a man was,” wrote Achebe, “if he was unable to rule his women and his children (and especially his women) he was not a really a man.” He beat his family members when they failed his expectations. On one occasion, he beat his youngest wife Ojiugo who was late cooking his dinner. The beating, however, took place during the Week of Peace when such behavior was forbidden. His kinsmen were displeased. To assuage the god Ani, Okonkwo had to bring an offering of livestock, cloth, and cowries to the god’s shrine.

Okonkwo was not merely harsh, he could be good father. When his favorite daughter Ezinma became ill, he gathered leaves for medicine. She was the only daughter of Ekwefi whose other nine children died in the first three years of their lives. According to tribal lore, when a woman loses her children at a young age it is thought that an ogbanje, an evil spirit, is inhabiting the children causing them to die so that it may born again in the next child. To discourage the ogbanje from returning, Okonkwo consulted a medicine man. He mutilated one of his dead children and buries the child in the Evil Forest to discourage the ogbanje from returning. Although he was not one to show affection, he felt compassion for Ekwefi. When a priestess took her only child for a night he joined Ekwefi in following the old woman to make sure Ezimna was safe.

Okonkwo’s life took an unexpected downturn when his gun exploded at the funeral of Ezeudu and the man’s 16 year old son died as a result. Even an accidental killing was an affront to the earth goddess and had to be atoned. Okonkwo and his family were exiled for seven years. They returned to his mother’s village Mbanta. His barns and homes were burned to the ground and his livestock slaughtered. Okonkwo’s life, writes Achebe, “had been ruled by a great passion—to become one of the lords of the clan. That had been his life-spring. And he had all but achieved it. Then everything had been broken.”

Nevertheless Okonkwo began again to plant a new farm but with little enthusiasm. Uchendu, his uncle, seeing that he had fallen in despair, encouraged him to take comfort among his kinsman.

In the second year of exile, Okonkwo’s friend Obierika brought him bags of cowies, their currency. He had sold the yams Okonkwo left behind. Obierka also delivered unsettling news; the nearby Abame clan was wiped out by white skinned foreigners.

It happened after a white man came on an “iron horse” into their village. The oracle told the village to kill the man lest he bring destruction. They killed him and tied his iron horse to a sacred tree. Sometime later three white men came to village, saw the motorcycle and left. Later a group of men came to the village on market day and shot to death everyone in the market. Only the elderly and disabled who were at home lived.

Sometime later six white missionaries came to Mbanta. Mr. Brown shared the Christian religion through an interpreter Mr. Kiaga. The clan dismissed the message as folly. When Mr. Brown asked for property to build a church, they gave him a plot in the Evil Forest assuming he would die within days. When he did not die, some of the clan became interested in the new faith. Some converted including Okonkwo’s son Nwoye.

The church grew as Christians took in outcasts and rescued abandoned twin babies. Mr. Brown was gentle and respectful. He counciled the converts not to antagonize the clan or show disrespect. He built a school and hospital and came to be respected by the clan.

Mr. Brown, however, was later replaced by Reverend James Smith who “condemned openly Mr. Brown’s policy of compromise and accommodation.” Smith did not preach restraint. Enoch, a zealous convert, taunted the clan by unmasking an egwugwu during a religious ceremony. Egwugwu, masked spirits, played an important role in the village. They represented ancestors and adjudicated village conflicts. The unmasking of an egwugwu was believed to bring death to the ancestral spirit and was considered a serious crime against the tribe. In response, egwugwu burned the church to the ground.

By this time, a white colonial government had built a court where a District Commissioner decided cases and a prison. The court employed messengers who were arrogant and high-handed toward the Igbo. The messengers guarded the prison and forced the prisoners to do menial cleaning and other tasks considered demeaning. The locals called them kotma, “ashy-buttocks” for the grey shorts they wore.

After the burning of the church, the District Commissioner asked the leaders of Umuofia to meet to discuss what happened. Rather than hear them out, they were handcuffed and jailed. The District Commissioner ordered them to pay 200 cowries. As soon as he left the building, the messengers abused the prisoners by shaving their heads, beating them, and refusing them food and water. The messengers demanded the clan pay 250 cowries or see their men hanged. When the village paid the ransom, the messengers pocketed the extra cash.

After the prisoners were freed, the men of the clan gathered to consider what they should do. When court messengers approached and ordered an end to the meeting, Okonkwo killed the lead messenger with his machete. He believed the other men would join him in armed resistance but the other leaders let the messengers to escape. Okonkwo understood then that times had changed and the clan was no longer willing to fight. The District Commissioner would never try to understand why the Okonkwo killed the messenger. He would not receive justice. He would never attain the honor and status for which he had worked his whole life. The rules had changed. What people valued had changed. What people honored and worshiped had changed. Okonkwo had no future. He could not change.

Okonkwo’s body was later found hanging behind his compound. His clansmen were by custom unable to take him down since suicide was considered an abomination. His kinsmen had to entreat the white men to take down the body.

The book ends with the musing of the District Commissioner who pondered how he would include the incident in a book he intended to write called The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger. The white man was completely ignorant of Okonkwo’s life, the depth of his losses, and the reasons for his death. When described in Commissioner’s book it would only underscore the inscrutable ways of the savage and the need for European enlightenment.

In truth Okonkwo’s loss was complete. As in Shakespearian tragedies, the character’s undoing was the result of a fatal flaw (fear of weakness and failure) and adverse circumstances. Okonkwo would have ended his exile, returned home, and rebuilt his farm had colonial powers not intruded. In particular, if the Reverend James Smith been more like Mr. Brown, Enoch would not have unmasked the egwugwu and the clan would not have burnt the church down. If the District Commissioner had taken the time to understand why the clan burnt the church instead of jailing them and forcing them to pay and if the messengers hadn’t humiliated the men and exhorted cash, the clan leaders would not have met to conspire against the colonial powers. Okonkwo would have hated the changes wrought by colonialization but would not have raised his machete. In the end, Okonkwo was not weak like his father but his strength was no longer valued by the community for they would not follow him into war.

Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart is a beautiful and tragic novel. It is valuable as a response to the European-centric writings about colonial Africa because it gives an African perspective. Africa cultures at the time were not inscrutable and savage. They had institutions and cultures different but not inferior to their European counterparts. They were no less no more human than those who would come to rule them.

The book as a fictional telling of the human response to social upheaval is also valuable because it is not particular to place and time but universal. People strive for status under certain rules. When the rules change, people may feel they can no longer attain their goals. People can adapt more easily to change that happens slowly and with respect (Mr. Brown) but rapid cultural change is disruptive and can be destructive to identity, status, and belonging. Colonialization brought some good change but negative aspects were especially harmful to identity (court system and messengers).

The challenge of social change is evident in contemporary American communities. The rise in drug and alcohol abuse, destitution, and suicide particularly among men may be indicative that such changes have been destructive to community and identity. What happens to a person’s mind when they can no longer attain the esteem of the community, when like Okonkwo, they feel they can never rebuild? Their strengths no longer have value. They can never go home.

Consider the changes wrought since 1990: End of the Cold War, rise of the Internet, ubiquity of social media, fracturing of news sources, increase in the types of entertainment media, most transactions done online, rising income inequity, greater political polarization, greater urbanization, less marriage and fewer kids, changes in the perception of gender and sexuality, and lower religious observance.